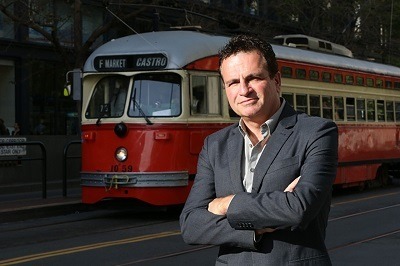

#Jay Mariotti Sports Columnist

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Jay Mariotti: Who's got it better? Harbaugh

He wasn’t on the ballot and has yet to coach a game at Michigan, yet Jim Harbaugh finished fourth in voting last week for the student-body presidency. This should shock no one who has watched life’s two proven equalizers, karma and justice, embrace him with hugs and love since Dec. 28. You’ll remember that as the dark and dirty afternoon when the 49ers — and there is no other way to state it — removed his khaki-covered carcass from the premises in one of football’s all-time mismanagement fiascos.

Those of us who know Harbaugh — me from way back — realize his public persona is something of an act. Yet no PR firm could shape a campaign that has him coming off as a happy, wealthy and enormously popular BMOC, in contrast to a Jed York-Trent Baalke corporate abomination that grows more sour and depressing by the hour at Levi’s Stadium. Seems Harbaugh makes more news than the Kardashians these days, the difference being that his events always glow with good, fun vibes, devoid of a Kanye or Disick funk.

“Disappointed w/4th place finish for @umich student body Pres,” he cracked Monday on his Twitter account. “Competitive juices flowing! Hat in the ring for 2016 & will campaign.”

Can a man beat Urban Meyer and rule a large student body in one swoop? Jimmy Frat House might be the only coach capable of pulling this off. It’s amazing how he keeps his personal headline cycle generating with cool water-cooler buzz that must warm the collective embittered souls of 49ers fans, who at least can root for Harbaugh from afar while their franchise implodes amid a crippling roster exodus and a bizarre coaching appointment. If he already had blown away York and Baalke in the public-opinion race, what’s happened since is a rout akin to the last Seahawks loss.

There was Harbaugh on a snowy afternoon in Ann Arbor, playing good Samaritan when he observed a rollover crash on an interstate highway. Christine Mowrer didn’t know who he was, but covered in blood after her 2003 Jeep Cherokee flipped at least three times, she was relieved to see Harbaugh and another football staff member wrap her and her 73-year-old mother in blankets and administer first aid until help arrived. “He probably kept me from going into shock,” Mowrer, 53, told the Ann Arbor News from her hospital bed. “I had blood dripping out of my nose, and he helped me out and got me onto the ground.”

Meanwhile, in Santa Clara, York and Baalke were trying to explain the identity of Jim Tomsula and douse speculation that Tomsula had undercut Harbaugh to get his job, furthering perceptions that the departed angel had been sabotaged by the worst kind of office politics. As Harbaugh said to a Bay Area columnist, “[You] definitely walk down the halls and people look away or they look at you and you know something’s going on,” adding that it would be a good issue for Tomsula to address. When Tomsula did address it, he blamed the media and never really denied it.

There was Harbaugh, going to Michigan basketball games, belting out the “Hail to the Victors” school fight song and pressing his hand against his heart during the national anthem. There was Harbaugh, staying in a budget hotel with his assistant coaches and eating pre-dawn cereal in the lobby before carpooling to Schembechler Hall and staying until midnight. There was Harbaugh, hanging out with his 25-year-old son, Jay, the new tight ends coach. There was Harbaugh, waving at students who wear “Maize, Blue and Khaki” T-shirts and “Welcome to Ann Arbaugh” clothing lines. St. Jim, they were calling him.

Meanwhile, in Santa Clara, York and Baalke were ducking reporters on a day when serious explanations were needed for fans. Why was Patrick Willis retiring? Why were Frank Gore and Mike Iupati leaving? Why was Justin Smith considering leaving? Why was yet another player in trouble with the law? Why wasn’t the highly regarded Vic Fangio given the head coaching job? And why was Tomsula babbling incoherently during a CSN Bay Area introductory interview?

There was Harbaugh, a big fan of the “Judge Judy” show, using his Twitter feed to congratulate Judith Sheindlin for signing a contract extension, to which she replied with a good-luck wish for his opening collegiate season. There was Harbaugh, hosting NFL prospects Jameis Winston and Bryce Petty for precombine workouts in what only could be a tribute to his standing as a quarterbacking guru.

Meanwhile, in Santa Clara, Baalke was denying reports he is shopping Harbaugh’s regressing pet QB, Colin Kaepernick. This while Kaepernick was engaging in Twitter wars and telling one fan, @battman_returns, to “mind your damn business, clown” and to “get better at life!” — all because one Stephen Batten had said Kaepernick’s abs workouts wouldn’t help him find open receivers, which is kind of true.

There was Harbaugh, escaping the Midwest winter for Arizona, coaching first base for the A’s as a “special guest instructor” for an old pal from his Palo Alto boyhood, manager Bob Melvin. And you know what he said after the Cactus League victory? “How does it get any better than this?” he gushed, in a variation of his famous line. “It’s a great day for baseball, and just to be able to put on the uniform … I haven’t been in a baseball uniform since American Legion ball.”

“He’s an inspiration just walking out here,” Melvin said. “He’s got that air about him. He’s always been quite the competitor and everyone knows that. A winner. And whenever you can have guys like that around, guys benefit from it. Plus you don’t find too many guys who want to get in uniform and go out there and interact with the guys during the workout.” Meanwhile, in Santa Clara, emerging defensive star Chris Borland was becoming an inspiration in his own right by retiring from football at age 24, injecting a cursed element into the raging chaos.

Given the turbulence and in-house leaks that undermined Harbaugh’s final season with the Niners, he deserves to experience a blossoming love affair at his alma mater. If York were an effective CEO, he would have made the Harbaugh-Baalke combination work and buffered their strained relations. The Seahawks have made it work with Pete Carroll and John Schneider, but instead of drawing lines for the coach and GM, York did the covenient management dance and sided with his fellow exec. I covered a fairly famous sports dynasty, the Chicago Bulls of the 1990s, that ended prematurely because an owner couldn’t soothe the differences between a general manager and a coach named Phil Jackson, who went on to win more championships than any coach in NBA history. Yet everyone weathered the storms long enough to win six titles, six more than these 49ers won.

“You have to have like-minded people building a team,” Baalke said in a media gathering after Tomsula’s first news conference. “If you don’t have like-minded people building a team, coach, coaching staff, front office … If we’re not all looking for the same characteristics, the same type of players, it’s tough to build a unit that can go out there on Sundays and win football games.”

We’re still waiting for York to say that he failed in letting the marriage collapse, in choosing a winner and a loser. Clearly, he wasn’t overly interested in appeasing Harbaugh after using his ultrasuccessful debut season to help get a $1.3-billion stadium built in Silicon Valley. The coach was too popular and wanted too much power, and regardless of his three consecutive appearances in the NFC title game, the big bosses wanted control and no tugging of the rope. Now, Baalke gets to pull the strings of his puppet, Tomsula, and tell him which assistants to hire and which players to acquire. Now, York can preside over his sterile, quiet stadium — the high-tech antithesis of Candlestick — and count megaprofits from Super Bowl 50, WrestleMania 31 and an outdoor hockey game.

Each party in this debacle has gained total control — Harbaugh in Ann Arbor, York and Baalke in Santa Clara. Yet only one man is going to win a lot of football games anytime soon. Someone asked Harbaugh if he viewed himself as the messiah of Michigan.

“I’m not comfortable with that at all,” he said.

Oh, yes, he is. Very comfortable.

Be happy for him. He deserves that much.

Mariotti is sports director and lead sports columnist at the San Francisco Examiner. He can be reached at [email protected]. Read his website at jaymariotti.com.

1 note

·

View note

Text

About Jay Mariotti Sportscaster

Jay sat down for a podcast interview conducted by Jason Barrett, an industry leader in sports media, and spoke candidly about his multimedia career and the state of the profession.

Jay Mariotti Sportscaster is one of America’s prominent sports commentators, known for his award-winning journalism, challenging opinions and passionate approach to sportscasting and sportswriting on all media platforms.

He has covered every major sports event nationally and worldwide on numerous occasions, including 14 Olympic Games and 26 Super Bowls, and has closely chronicled all the major newsmakers and issues of his time.

In its September 2014 edition, GQ magazine all but accused me of extortion in an absurdly false report — claiming I used a camera-phone video of an ESPN executive to coerce the network into giving me assignments. It is a lie that would be laughable if not so damaging and such a reckless disregard of the truth. The author of the GQ story, from the trashy Deadspin site, never bothered to contact me or my representatives about this allegation and apparently didn’t bother to check a Deadspin story about the matter that never connected me to a camera-phone video.

In the lobby of the Twitter building, which is near the Uber building and the Dolby building and a residential tower where $5,500 a month will get you 969 square feet and a parking spot, I visit a gourmet market that makes Saison look like Burger King. I examine a $75 bottle of 2007 Fiorita Brunello, check out a $67 jug of French lavender shampoo, consider a $130 slab of Jamon Iberico Pata Negra (“pure acorn fed Iberian pigs”) and settle for a $6 ice cream cone. Then I stroll outside, absorb the glory of a blue-skies-and-71 afternoon, head across Ninth Street … and have to weave and shake like Steph Curry to avoid a fresh puddle of bubbly urine.

He could be commenting one minute on the NFL’s morality crises, the next on why greedy sports leagues and TV networks are gouging viewers and jeopardizing the industry long-term, the next on why Lambeau Field is the best venue in American sports, the next on why Steph Curry and J.J. Watt are the new American dreams, the next on why we should pay more attention to the Iditarod. It’s vital to have independent voices who aren’t stifled by institutional filters.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Jay Mariotti Best Sports Commentator in Santa Monica, CA

Welcome to the latest installment of "Unmuted," the most credible and topical podcast in sports media, hosted by the accomplished commentator who spent 17 years as a dominant Chicago columnist and eight years as a daily panelist on ESPN’s ``Around The Horn.’'

Jay sat down for a podcast interview conducted by Jason Barrett, an industry leader in sports media, and spoke candidly about his multimedia career and the state of the profession.

Mariotti is the host of ``Unmuted: The National Sports Podcast,'' addressing the day’s sports topics in his commanding style inside a brisk, 30-minute audio window. "Unmuted" is available on download sites at Apple, Google Play and Podbean and at jaymariotti.com.

His most visible work includes eight years as a regular daily panelist on ESPN’s TV debate show, “Around The Horn,” and 17 years as Chicago’s dominant sports columnist. Later, he had a successful run as sports director and columnist at the San Francisco Examiner, where he won 2016 praise for column writing in the California Newspaper Publishers Association contest.

He also has written a book about his life and career, “The System,” published by Amazon. And he became one of the first Jay Mariotti sports commentator to develop multimedia content — daily radio show, full-length columns, topical videos and podcasts — for a national independent website in 2013-14. “The System” in part chronicles a court case involving false allegations that were dismissed and expunged by a Superior Court in Los Angeles, meaning Mariotti was not convicted. A 2012 civil case against Mariotti failed and was dropped.

In the media profession, Jay Mariotti is regarded for his wide range of topicality and myriad experiences. He could be commenting one minute on the NFL’s morality crises, the next on why greedy sports leagues and TV networks are gouging viewers and jeopardizing the industry long-term, the next on why Lambeau Field is the best venue in American sports, the next on why Steph Curry and J.J. Watt are the new American dreams, the next on why we should pay more attention to the Iditarod. It’s vital to have independent voices who aren’t stifled by institutional filters.

Mariotti fills the void, recognizing that sports has taken complex and unprecedented turns and why the need for robust, serious commentary and investigative reporting is stronger than ever. Sports should be covered by commentators who are editorially and financially detached from the big mechanism, respectful that the fan also is a consumer who invests his passions, his mind, his time … and his wallet. Mariotti never has forgotten that.

1 note

·

View note

Link

Yes!

Via Tom Ley, posted 10 Sept 2020:

This site exists because of the events of Oct. 29, 2019, when we all still worked at Deadspin.

That was the day that Barry Petchesky, who had been a writer and editor at the site for over 10 years, and was at that point the site’s acting editor-in-chief, was fired. He was marched back to his desk by G/O Media CFO Tom Callahan, who made Petchesky hand over his keycard and collect his things while I and a handful of my colleagues demanded to know why he had just been fired. We’d all sprung up from our chairs and started barking half-formed questions, to which Callahan responded by pointing at one of our computers and sneering, "Just look at the home page.”

At that moment, Deadspin’s home page featured stories about wedding dresses, three good dogs I recently met, a pumpkin thief—and no stories about sports. This was purposeful, the staff’s response to a memo sent by the company’s executive editor a day earlier that forbade us from covering topics not related directly to sports. Jim Spanfeller, who had been installed by the private equity firm Great Hill Partners as CEO of our company all of seven months before, responded to this act of insubordination by calling Petchesky into his office, firing him, and then telling him to “get the fuck out.”

I spent the rest of that day and most of the next huddled in an empty corner office with my colleagues 27 floors above the 45th and Broadway intersection of Times Square. The conversations we had in that room eventually led to all of us making the decision to quit in solidarity with Petchesky.

At this point the staff was used to navigating various workplace crises. We’d had similar meetings before, following resignations, sales of the company, layoffs, collective-bargaining sessions, and even a bankruptcy. We used to joke about how no new Deadspin employee ever made it through their first few months at the site without some kind of company-wide crisis.

This meeting felt different, though. Through all the other troubles we had been able to determine that no matter what was crumbling around us, Deadspin was still ours, and the ability to go to work every day and make the website we loved was worth holding onto for as long as possible. But suddenly we were confronted with a vision of Deadspin’s future—one without Petchesky and without the editorial freedom our site depended on—that we simply couldn’t accept.

One colleague, vaguely recalling all the other existential threats we’d survived through the years, summed up our situation neatly, saying through his tears, “They got us this time.”

Within 48 hours the entire remaining staff of Deadspin, 20 people, had resigned. Now, 10 months later, we are ready to start something new.

That’s the story of how we arrived at this point, but if you want to truly understand why we are doing this, you need to widen the scope a little bit. The full story is about more than just an irascible staff of writers reacting flippantly to a memo they didn’t like. It’s a story about what will and won’t be tolerated, both by those with the power to shape the present and future of the media industry, and by those who bear the consequences of how that power is wielded.

The version of Deadspin we walked away from was an immensely popular one. Every day, millions of people visited our site—by the end, a good month saw us bringing in around 20 million unique visitors—to see what we had to show them. You could log on in the morning to read analysis of a hockey game, come back a few hours later to a perfectly crafted headline about Lions fans copulating in a parking lot, and then return in the evening to find out that Manti Te’o’s dead girlfriend was a hoax, or why Greg Hardy was arrested, or what kind of person NBA All-Star Kevin Johnson really is.

Every day offered Deadspin an opportunity—to joke, to argue, to critique, and to uncover. The tenacity with which we seized that opportunity is what electrified the site.

Deadspin didn’t acquire all those readers by accident, and the skills its writers and editors needed to run the site every day didn’t spring from nothing. The site grew and became a better version of itself every day because of how seriously those who were entrusted with it guarded and improved upon the folkways and traditions that had been handed down by previous iterations.

Will Leitch launched the site in 2005, and from the very start gifted Deadspin with a clarity of purpose that persisted right up until our departure. The site’s motto from its 2005 launch until our last day: “Sports news without access, favor, or discretion.” In one of his first posts Leitch explained, “There’s a whole side of sports that, because of either corporate obligations or just plain laziness, never makes it into the public consciousness. We specialize in that side.”

After Leitch came A.J. Daulerio, who understood that the more Deadspin burrowed itself into the negative space created by traditional sports media institutions, the more vital the site became. Deadspin looked at ESPN and newspapers and other legacy publications the way raiding Vikings must have looked at the shores of Britain, dedicating an entire section to exposing workplace harassment at ESPN, revealing sports media stars like Jay Mariotti and Sean Salisbury as frauds and hacks, and routinely securing stories in ways that would make a journalism professor faint.

Those infamous pictures of Brett Favre? Exchanged for a paper bag stuffed with cash.

Tommy Craggs succeeded Daulerio, and during his tenure Deadspin’s already venomous bite was imbued with a political sensibility. The scope and ambition of the site also began to expand during Craggs’s tenure, and eventually the site that had started with a staff of one accumulated a stable of editors and writers, reporters with dedicated beats, as well as the budget and appetite needed to publish the sort of reported scoops and features that rivaled anything you’d expect to find in a prestigious newspaper or magazine. The site also established culture and lifestyle sections, which brought Deadspin’s voice and point of view to bear on all manner of topics, like Gamergate and Wile E. Coyote.

A funny thing started happening around this time: The site that had stood itself up by throwing bombs at various institutions was becoming something of an institution itself. This transformation continued under the stewardship of subsequent editors Tim Marchman and Megan Greenwell, both of whom worked to diversify the staff, further expand Deadspin’s coverage areas, and continue landing the sort of big, industry-leading stories that made the site an indispensable daily read.

After a while it was no longer accurate to describe Deadspin as just a sports site (though the vast majority of its coverage remained sports-related) or as a place to find rude headlines about sports columnists. What Deadspin became, what it was on the day its entire staff resigned, was a full-bodied publication. It married muckraking with a 27-word blog post headlined Tony Dungy Doesn’t Think Michael Vick Is Being Haunted By Dog Ghosts.

To an uncommon extent, readers wanted to know what Deadspin had to say. When other people in the industry would hear about how much of our traffic came directly through the homepage (as opposed to social media or search), they would stare in disbelief. Whenever someone left the site to go work at another outlet, they would invariably send a grim dispatch about how much they missed Deadspin’s built-in audience.

What was apparent to those of us who had spent years reading and creating Deadspin was that the site wasn’t defined by what it covered, but by its sensibility.

People liked reading a site that refused to condescend or patronize, that was comfortable telling ugly truths about sports and the world at large, that was rude, that was mean (usually in ways that were more illuminating than gratuitous), and that was whimsical in ways that were never insufferable. Readers didn’t come to Deadspin every day just to get their sports news or find out who won last night. They came because they liked reading Deadspin.

Where did it all go wrong, then?

There are perhaps too many points on the timeline to discuss. Maybe it was when infamous venture capitalist and Donald Trump confidant Peter Thiel, angered over sister site Gawker’s antagonistic coverage of him, secretly funded a lawsuit against Gawker Media from ex-wrestler Hulk Hogan and structured it to cause maximum damage to the company. (A loss at trial in Florida state court in March 2016 resulted in a $140 million judgment and Gawker Media’s bankruptcy.) Maybe it was when debt-laden broadcaster Univision bought the company at auction that August and then spent the next few years failing to figure out exactly what it wanted to do with us. (To wit, Univision seemed to be under the impression that Gawker Media’s sites would somehow be able to create television shows that would prop up their failing cable channel, Fusion.)

Even if the dominoes started falling years ago, I never felt the end was in sight until Great Hill purchased the company in April of 2019. They got to work quickly, changing our name to G/O Media, and installing Spanfeller, a veteran of Forbes.com and content mills like The Daily Meal, as CEO. During his introductory meeting with the whole staff, he revealed that though he’d spent his career on the business side of digital media, his true ambition was to publish the next great American novel.

Spanfeller moved through the office like a blunt object, always more interested in how to further monetize the G/O Media sites than in the sites themselves. In an early meeting Spanfeller had with the editorial staff, he told us that his plan was to more than double G/O Media’s annual revenue within a year.

He went about executing his plan by firing the company’s top two editorial leaders, wiping out the investigations desk, and installing a coterie of former colleagues in high-level positions across the company. As Spanfeller molded the company to fit his vision, we at Deadspin found ourselves in a heated confrontation with him.

[…]

Soon it became clear that his plan for juicing G/O Media’s revenue involved turning Deadspin into the kind of site it was never supposed to be. He liked to talk about the site’s position in the “sports category,” kvetching about how poorly our revenue and traffic numbers stacked up against those of ESPN.com and SB Nation.

It didn’t seem to matter to him that sports fans would visit ESPN.com and Deadspin for entirely different reasons, or that every site ahead of us in the “sports category” had exponentially larger staffs, or that some of those same sites relied on hundreds of underpaid and unpaid bloggers to hit their traffic numbers, or that Deadspin was one of the few sites that earned its traffic without resorting to SEO plays designed to capture clicks from people searching things like “Mayweather vs. McGregor livestream.”

None of that seemed to matter to Spanfeller, because he didn’t see Deadspin the way its staff and its readers saw it. To him it was just a valuable brand name within the sports category, and with that brand name came unlimited potential for growth and profit.

[…]

Lately I’ve been thinking of Deadspin as a strange machine. For more than a decade, the people charged with the maintenance of that machine were allowed to tinker with it according to their whims and idiosyncratic tastes. The result of all that tinkering was a machine which, for all its apparent wonkiness, worked brilliantly.

The problem with a machine like that is that it’s difficult for anyone who didn’t build it, or doesn’t respect those who did, to understand exactly how or why it works. When Deadspin’s staffers and readers looked at the machine, they saw a wonderful and whirring contraption, but all Spanfeller and Great Hill saw was an odd collection of valves and pistons. They saw parts, but not the whole.

Spanfeller’s disdain for his own newsroom, the “stick to sports” memo, Petchesky being fired, and the cascade of oppressive ads—they were all signaling the same thing: Spanfeller and Great Hill weren’t really interested in preserving what we had spent the last decade building. Maybe a few components would remain to keep up appearances, but Deadspin’s demolition was coming, and we couldn’t stop it. What we could do was refuse to participate in its destruction.

What happened at Deadspin, what’s still happening at G/O Media, isn’t unique. It’s just a particular version of the same slow-motion, industry-wide disaster that’s been unfolding for years.

[emphasis mine]

Everything’s fucked now.

Newspapers have been destroyed by raiding private equity firms, alt-weeklies and blogs are financially unsustainable relics, and Google and Facebook have spent the last decade or so hollowing out the digital ad market. What survives among all this wreckage are websites and publications that are mostly bad. There’s plenty to read, the trouble is that so much of it is undergirded by a growing disregard (and in some cases even disdain) for the people doing the actual reading.

What readers are being served when a sports blog leverages its technological innovations in order to create a legion of untrained and unpaid writers? Who benefits when a media company cripples its own user experience and launches a campaign to drive away some of its best writers and editors? Whose interests are being served when a magazine masthead is gutted and replaced by a loose collection of amateurish contractors? Who ultimately wins when publications start acting less like purpose-driven institutions and more like profit drivers, primarily tasked with achieving exponential scale at any cost? What material good is produced when private equity goons go on cashing their checks while simultaneously slashing payroll throughout their newsrooms?

Things have gotten so bad that even publications that get away with defining themselves as anti-establishment are in fact servile to authority in all forms, and exist for the sole purpose of turning their readers into a captive source of profit extraction.

The truth is that nobody who matters—the readers—ever asked for any of this shit. Every bad decision that has diminished media—every pivot to video, every injection of venture capital funds, every round of layoffs, every outright destruction of a publication—was only deemed necessary by the constraints of capitalism and dull minds.

This is an industry being run by people who, having been betrayed by the promise of exponential scale and IPOs, now see cheapening and eventually destroying their own products as the only way to escape with whatever money there is left to grab.

The ability of Defector to escape these constraints will depend not only on the quality of our work, but on our ability to avoid feebly chasing dollars through a collapsing digital ad economy. We want the freedom to provide you with a site, custom-built by our partners at Alley Interactive, that isn’t clogged with pop-up ads, banner ads, video ads, and chum boxes full of spammy headlines explaining how That One Girl From Full House Looks Like A Damn Snack Now.

Me:

Nothing lasts forever, not even tumblr, and probably not even Defector. I gave ‘em a lousy $8 this month. Hopefully I can continue to do so.

Defector’s prospects are grim, not at least because of ALL THE OTHER sporps blergs out there plus the Second Great Depression now underway. How will it end? Sued into oblivion like gawker was? Unable to find enough subscribers or advertisers to fund operations? No search traffic from google? Buried by the algorithm on facebook? The worrying starts IF defector is viable (ie: people have money to give) and churns out not just great stories and thinkpieces but also good #content to goose the Google and Facebook algorithms. Who knows where things will be in a year.

Here’s the thing IMO: The business elite, the billionaire class, social conservatives from every income bracket, GOP acolytes, and our reviled gatekeepers at facebook & google, all are in unison on the notion that what’s posted online must be controlled.

What’s posted online should never impinge upon their collective dominance. Authority, especially THEIR authority, must never be questioned. Even one’s inclination to question authority must be countered by intimidation and fear. We, you and I, can have some left-ish “capitulzm sux” schtick, as a treat, but any and all critical writings on the powers that be and the way things work, anything that raises deeply pertinent and uncomfortable questions on the people who have accumulated outsize power and control over the course of our lives, that must be clamped down upon post-haste.

Peter Thiel and crew successfully went after gawker’s survival, and its select shitty posts from shitty people were a conveniently compelling argument that the website needed to go (not just the shitty people). Later revelations made the case that much more was at play, somewhat vindicating the suspicions of Gawker’s good writers.

As Gawker has noted over the past decade:

[Thiel’s] vaunted hedge fund Clarium Capital was an abject failure, losing more than 90% of its $7 billion in assets, a decline that Valleywag assiduously chronicled.

He is an arch libertarian who believes that central mechanisms of contemporary society—including representative democracy, universal suffrage, and formalized education—are either outdated or incompatible with human freedom.

He is a loud proponent of “seasteading,” the movement to establish sovereign communities on permanent ocean vessels for the purpose of developing legal systems unencumbered by taxes or any other kind of traditional government policies.

He believes death itself can and should be cheated, and even intends to be cryogenically frozen after he passes away, in hopes that science will one day be capable of reviving him. He literally wants to live forever.

He has backed efforts to question the legitimacy of climate change science as well as political groups opposed to immigration—even though the industry that minted him as a billionaire is heavily dependent on immigrant labor.

Gizmodo’s recent coverage of Facebook, in which Thiel was an early investor and on which he has a board seat, launched a congressional investigation into the company’s news curation practices, and inspired a national conversation about the vast amount of power the company wields—with no transparency and minimal accountability—over who reads what.

These stories, which are only a small sample of those Gawker has published about Peter Thiel, largely concern his professional life: Business ventures, political positions, and public statements. But as he noted to the Times, it was concern for his “friends” that Gawker had covered that motivated his secret legal assault: “One of my friends convinced me that if I didn’t do something, nobody would.”

Hm.

The news business is indeed in dire straits right now. As noted above in the defector blerg post, it’s definitely true that:

“Every bad decision that has diminished media—every pivot to video, every injection of venture capital funds, every round of layoffs, every outright destruction of a publication—was only deemed necessary by the constraints of capitalism and dull minds. This is an industry being run by people who, having been betrayed by the promise of exponential scale and IPOs, now see cheapening and eventually destroying their own products as the only way to escape with whatever money there is left to grab.”

I contend that THIS IS THE PLAN. No news, after all, is good news. Money of course is made, “profit extraction” and/or “value extraction” happens, but these companies are one part cynical profiteers but also one part ideologues: an informed electorate is BAD. Fuck this, the public doesn’t need to know jack shit about anything.

Via The New Republic, posted Oct 2019:

This is not to further pan for lamentations over the demise of a website. Splinter and its parent company was already something of a distressed asset—its status as such, in fact, likely played no small role in attracting the attention of Great Hill in the first place. But the wider world of mass media is filled with other such distressed assets, from the websites spawned in the heyday of venture capital media mavens, to long-standing local and regional newspapers, straining to balance their journalistic mission with an ever decreasing supply of capital.

It feels increasingly like the terms of journalism—which kinds of outlets get to do it, who gets paid enough to live doing it, which communities get coverage—are set by the rich.

The best case scenario is that journalists become part of a billionaire’s patronage network.

When Splinter shuttered, former Gawker writer Brendan O’Connor wrote that “the workplace under capitalism is a dictatorship, and the dictatorship of private equity is an especially arbitrary one.” It’s a shame that journalism—something with such obvious broad societal value, and that should be wholly antagonistic to the rich and powerful—should be mostly done for private profit, with all the compromises that come with that. But the sad fact of journalism’s dependence on profit-making becomes far more grotesque and dangerous when the profiteers in question are financial sector wheeler-dealers.

This particular flavor of profiteers seek a higher yield, faster, with no regard for the long-term sustainability of the business.

Alden Global Capital, which owns Digital First Media (DFM) and its publications like The Denver Post, drained hundreds of millions of dollars from DFM for their own gain. It can be confounding to contemplate: How can a hedge fund profit from destroying the value of what it just bought? Remarkably, they can.

As The American Prospect explainedin detail last year, private equity can make big bucks off destroying local papers if it “strips staffing and siphons off cash flow.” Papers continue to make money off local advertisers who still value them, even as the quality of the journalism collapses; cutting costs by laying off staff or centralizing production can speed it up. Essentially, the long-term consequences to profits don’t catch up fast enough to prevent the hedge fund owners from stripping the assets, who then flip the carcass.

That’s how you end up with instances in which Alden executives “rewarded themselves with tens of millions of dollars’ worth of prime real estate in Florida and the Hamptons for their personal enjoyment.”

The “War on Journalism” isn’t a myth, it’s a bone fide pursuit. There has never been a “liberal media” and the corporations that own news organizations very much prefer it stay that way. Facebook and google siphoning away ad dollars helps immensely to this end.

Take Advance Publications and the Newhouse family!

Via the CJR, posted Dec 2013:

Often represented to employees as an extraordinary worker benefit, The Pledge, in fact, had its roots in the antipathy of the late Advance founder S.I. “Sam” Newhouse, Sr. toward organized labor.

“I refuse to stand by passively and allow any union to ‘bust’ me,” he wrote in A Memo to My Children, a thin, self-published memoir that is apparently the only personally penned record of his life and career.

After acrimonious and sometimes violent contract negotiations and strikes at Advance-owned newspapers in New York, Oregon, Missouri, and Ohio in the 1930s through the mid-1960s, Sam Newhouse, apparently in consultation with his son, Donald, is believed to have crafted the Pledge. (The Newhouses have declined to talk to reporters and authors about the Pledge, including me when I was researching my recently released book about the “digital first” changes at the Times-Picayune and other Advance newspapers.)

Over the years, the Pledge became “so well-known throughout the newspaper industry that it was almost considered legendary,” according to a 2009 lawsuit by former Mobile, AL, Press-Register Publisher Howard Bronson, who sued after he was dismissed from his $745,000-a-year post at the Advance paper while The Pledge was still in force. (The suit was settled for an undisclosed amount in April 2011.)

When originally instituted in the mid-1960s, The Pledge explicitly promised employees that they would not lose their jobs “because of technological changes or economic conditions so long as the newspaper continues to publish and [employees] are willing to retrain for another job, if necessary.”

It was modified in 2008 to cover only permanent, non-union employees of Advance’s daily newspapers “published in newsprint form.” The addition of this fine print set the stage for the arrival of the digital initiative, which began in 2009 at the Newhouse-owned Ann Arbor News in Michigan. Layoffs were now technically permissible under the still-in-force Pledge because that newspaper went from daily to twice-weekly. And in July 2009, 214 jobs were eliminated at the Ann Arbor News.

Advance rescinded The Pledge altogether in February 2010, when the newspaper industry was deep into its long and ugly nosedive.

“We felt that it was the right thing to communicate to people that we could no longer afford not having the flexibility to do something if the revenue challenges continue,” Steven Newhouse told The New York Times in August 2009. “I think the policy was meant for a time when the newspaper business had ups and downs, but was relatively stable. It was not meant for a time when our newspapers, like others, are struggling to survive.”

…

Deadspin, amongst its furious shitposting, and kinda like gawker (when it wasn’t fucking shitty), spoke truth to power.

There is a concerted effort to end that, online and elsewhere.

There’s a concerted effort to control what’s posted online and what information can be freely accessed.

(my bad and shitty theory: The overarching, unifying reasons are power, control & domination. Conservatives want far-left views that threaten them to be vanquished, businesses want preferential treatment to do whatever the fuck they want, the billionaire class want their wealth protected from the guillotines of the working class, the GOP wants political power in perpetuity, Facebook & Google are run by rapacious ghouls and ideologues. ALL OF THEM want control over what becomes public information and #content just for their individual safety from the rebellious unwashed masses, as recent advances in AI will mean a lot less people employed anywhere, and that + climate change = guillotines for the rich.)

TL;DR: Corporate media sucks. Check out Defector.

#long post#scroll alert#news#defector#sporps#journalismism#us press corps#news media#the media#corporate media#gawker is dead#long live gawker#deadspin#g/o media#gawker media#the news business#the way things work

1 note

·

View note

Text

Unmuted: The National Sports Podcast with Jay Mariotti

Tired of shallow, amateur sports podcasts? Jay Mariotti, the accomplished columnist and commentator, is the host of "Unmuted: The National Sports Podcast", addressing the day's topics in his commanding style inside a brisk, 30-to-40 minute audio window.

Welcome to the latest installment of "Unmuted," the most credible and topical podcast in sports media, hosted by the accomplished commentator who spent 17 years as a dominant Chicago columnist and eight years as a daily panelist on ESPN’s ``Around The Horn.’'

Mariotti is the host of ``Unmuted: The National Sports Podcast,'' addressing the day’s sports topics in his commanding style inside a brisk, 30-minute audio window. "Unmuted" is available on download sites at Apple, Google Play and Podbean and at jaymariotti.com.

He also has written a book about his life and career, “The System,” published by Amazon. And he became one of the first sports commentators to develop multimedia content — daily radio show, full-length columns, topical videos and podcasts — for a national independent website in 2013-14. “The System” in part chronicles a court case involving false allegations that were dismissed and expunged by a Superior Court in Los Angeles, meaning Mariotti was not convicted. A 2012 civil case against Mariotti failed and was dropped.

Mariotti fills the void, recognizing that sports has taken complex and unprecedented turns and why the need for robust, serious commentary and investigative reporting is stronger than ever. Sports should be covered by commentators who are editorially and financially detached from the big mechanism, respectful that the fan also is a consumer who invests his passions, his mind, his time … and his wallet. Mariotti never has forgotten that.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Lightning Rod of Sports Journalism Explains What on Earth He's Doing In San Francisco

In the lobby of the Twitter building, which is near the Uber building and the Dolby building and a residential tower where $5,500 a month will get you 969 square feet and a parking spot, I visit a gourmet market that makes Saison look like Burger King. I examine a $75 bottle of 2007 Fiorita Brunello, check out a $67 jug of French lavender shampoo, consider a $130 slab of Jamon Iberico Pata Negra ("pure acorn fed Iberian pigs") and settle for a $6 ice cream cone. Then I stroll outside, absorb the glory of a blue-skies-and-71 afternoon, head across Ninth Street ... and have to weave and shake like Steph Curry to avoid a fresh puddle of bubbly urine.

That shower, truth be told, is among many reasons San Francisco is the best place to write in our thrive-or-die republic. It was left by a shouting homeless man whose pants are undone, one of thousands whose blighted survivalism is juxtaposed against the backdrop of the city's new rich. For a writer, this social clash is literary gold. I said as much to my new editor-in-chief at the Examiner — "You should have someone just walking up and down Market Street every day" — and, for a moment, I thought I should be the man for that beat. Who wouldn't want a daily pass to view kid tech wizards getting off trains and striding past the encampments, addicts, and other sad stories? Or, in SoMa and the Mission, watching the homeless hassle the techies as they board, rock-band-style, Silicon Valley shuttle buses to Google and Yahoo and Apple and Facebook?

But I am not here to cover gentrification and other ongoing dramas in the most complex and compelling of American cities. I am here to explore a sports scene that, in a different context, is no less fertile for creative material. After a career intermission that had more to do with catching my breath — roughly 7,000 columns and 1,700 ESPN TV appearances, hundreds of radio shows, 14 Olympic Games, 24 Super Bowls, travel to five continents — than a recklessly reported legal case, I find no greater reward than resuming my commentary in the Bay Area, where the striking beauty and exhilarating mystique are accompanied by what we in the Jay Mariotti Sports Columnist media call great shit.

Last time I had the potential for this much fun, Snoop Dogg was staring me down before an "Around The Horn" taping, saying, "Who do you think you is?"

San Francisco has been the place for flower children, poets, gold-rushers, tech dreamers, drifters, politicos, and reinventists. Now, I dare say, this is the place for sportswriters. In Chicago, a previous stop of 17 years, I often bemoaned lousy owners and bad teams who were in bed with corrupt media, including two baseball franchises that have won one World Series over a collective 203 seasons. Here, the immaculate Giants have won three in five years, a near-impossible run in the sport's subsidy-driven parity era, while giving giddy fans a delightful roster of characters ranging from a Mad Bum to a Buster to a Freak to a scooter-driving hipster to a bitterly departed Panda.

Here, the Warriors play the most exciting basketball on the planet, led by the incomparable Curry, whose swag and splash on the court are matched by his decorum and charity work off it (as His Barackness quickly figured out and glommed onto). Here, the formerly regal 49ers are in a chaotic and cursed freefall, thanks to a front office that (1) allowed internal politics and professional resentment to subvert Jim Harbaugh's ultra-successful reign; (2) chose a curious successor in tongue-tied, unproven Jim Tomsula; (3) absorbed a mass exodus of high-character leaders; and (4) watched helplessly as Chris Borland, my early leader for Sportsman of the Year, prioritized his long-term wellness over his prowess as a 24-year-old linebacker.

Here, the A's remain the quirky darlings whose winning defies reason and whose brilliant, Hollywood-famed GM, Billy Beane, finally may have outmaneuvered himself into a pretzel after trying to win it all last season. Here, the Raiders are at a low point in on-field cred as they threaten to move yet again, which, ideally, would hasten a gutting of the Coliseum — weep, you costumed loons — and lead to a new baseball-only park that restores the beautiful hillside views of yesteryear. Here, you have David Shaw, the coach the 49ers should have hired, mixing football prominence with Stanford's cooler-than-Harvard academic boom. Here, you have a maddening hockey franchise owned by someone who may or may not exist.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Jay Mariotti Sports Columnist

https://wootake.com/watch_video.php?v=61O5U2XOON16&utm_source=dlvr.it&utm_medium=tumblr&utm_campaign=wootake%20media%20network

0 notes